by Ellis Aferi, Ghana

[From the SGI Quarterly]

After my secondary education, I was employed as a village teacher in Ghana. I was expected to live an exemplary life as a Christian, and I even shared my meager salary with the poor. When I discussed my poverty with the local priest, I was told it was caused by witchcraft in my family. I resorted to drinking, thinking that this would at least make me feel better.

Because of my heavy drinking, I lost my job, and then consulted juju men and so-called spiritualists. I was told that witches had planted a barrel in my stomach, which was why I was drinking so much! They performed ritual after ritual, but to no avail. Eventually I left the village to escape the witches. So, in June 1974, I came to the harbor city of Tema to start a new life. Within two weeks I had a job at the Volta Aluminum Company.

On my birthday, June 15, I happened to meet my cousin, who invited me to a Buddhist discussion meeting that night. I accepted this new faith because I believed it could protect me against the "witches" and remove the barrel in my stomach. The chanting I did at the meeting gave me new hope and joy. But the next day, to my shock and dismay, I was informed that I had been dismissed from work. I blamed my cousin for leading me to misfortune with his religion.

I went from my work place to the home of the Buddhist leader I had met the night before, and complained bitterly. But he encouraged me, saying, "Unless one changes one's evil karma now, one will keep coming back to suffer the same misfortune eternally." He gave me some reading material which put new life and hope into me.

I continued to attend Buddhist meetings and read a lot to convince myself of the practice. After two years I was appointed a local leader and soon got a new job with an attractive salary. I began to see the proof of my practice. I then met Rose, the lady who was to become my wife. We were married in a Buddhist ceremony in 1977. I resigned from my job, and we set up a soap manufacturing company together.

But in 1986 things took a drastic turn. Our business collapsed and we went bankrupt. We could neither pay our rent nor settle any bills, and my wife was by then expecting a baby. We moved out of Tema to live on land we had previously purchased for farming.

It was underdeveloped; no water supply or electricity, no neighbors in sight. During the rains, the roof leaked and it was a very difficult time for my wife. It was a struggle to find enough money to eat. But we survived, and the more perilous our situation became, the stronger was our resolve to chant.

In September 1986, after a difficult labor and successful surgery, our son Kofi was born. But a month after his birth, he started crying day and night. He was diagnosed as having a hernia, and he too had to undergo surgery.

We had no money for the hospital bills and chanted to the Gohonzon (our Buddhist object of devotion) day and night for a solution. After the operation there wasn't even a bed for him and we had to take him home, to return after five days for the wound to be dressed. This was the benefit we had chanted for. On the fifth day the doctor found that the wound had completely healed.

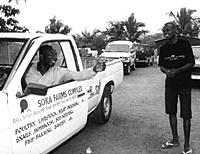

Our Buddhist practice was

our only source of hope at this critical time. We had just our two-and-a-half-acre

plot, and with the carpentry, plumbing and masonry skills I had learned

during the construction of the SGI-Ghana Community Center, I built a small

piggery and some poultry houses without any knowledge or experience of

poultry farming. I plunged into poultry with some 10 birds, while my wife

sold bread. This was the beginning of the Soka Farms. I wanted to prove

that one could start a farm or business without necessarily relying on

the bank or the government for assistance.

The African farmer is the

most deprived and impoverished agriculturist on the globe. He still has

to use rudimentary implements, rely on rain, has little access to fertilizer

and improved seeds, and has no credit facilities to enable him to expand

his farm to commercial levels. In effect, the African farmer produces mainly

to feed himself and his family.

But, with the support and encouragement of my wife and my son Kofi, I resolved to become a successful agriculturist so that my story would inspire idle youth to take up farming.

I realized that I could achieve nothing without discipline, determination, good management practices, faith and hard work. I had to persevere and overcome all difficulties. But I realized that I could not investigate the areas that interested me, the production of nontraditional agricultural produce, such as mushrooms, rabbits, honey, snails and fish, without training or experience. So I asked the advice of agricultural extension officers. One man in particular, Mr. Nukpor, was very supportive. He gave me useful information on scientific ways of production, record-keeping, and farm management. I virtually became a student again and was delighted to learn. I also attended seminars and workshops to learn about the latest scientific research.

Earning small amounts of money from the sale of the fowl, eggs, and animals, I developed the mushroom project, honey production, rabbit and snail breeding, and a fish farming project. It was very difficult, and progress depended on the slow and painful method of plowing back small profits into the venture and waiting for yield. There was no financial assistance to speed up the pace of development.

After many ups and downs, I am happy to state that, with undying faith, we have succeeded in raising our life condition, and our family is living harmoniously in our village after 24 years of practice. This is a dream we never imagined could become a reality. Remembering that "Buddhism is win or lose," and determined never to lose, we persevered in our struggle and never gave up until things began to change for the better.

The crown of our determination and hard work came in 1996 when we won the Best Farmer Regional Award, Tema. The farm is well integrated, leaving virtually nothing to waste. The field crops provide residues for the ruminants. The ruminants provide valuable farmyard manure for the field crops and vegetables, and the nonruminants provide fertilizer for the aquaculture system. The fish provide valuable proteins for the family, and the bees provide healthful honey, and so on.

This award was a wonderful honor for Soka Farms which started as such a tiny backyard venture. Our success story has been featured in a number of newspapers, and farmers, students, and youth who want to go into agriculture come here daily to gather information on aspects of farm management. I am determined to open the doors of my farm to the youth of Ghana so they can learn to adopt a practical and innovative approach to life through training in practical integrated farming systems.

Without the courage derived from my Buddhist faith, I would have given up altogether. I had a family to look after, children and dependents to educate. It was difficult to combine all these with such slow-pace farming. Most of the time I was penniless.

However, guided by the principle of "Never give up under any circumstances," I forged ahead, chanting for the Buddha's virtues of courage, wisdom, life force, and fortune to enable me to break through all barriers.

I was determined never to

lose, in order to demonstrate actual proof of my faith to motivate the

youth of SGI-Ghana and show that no matter what, with faith one can change

poison into medicine. SGI President Ikeda has asserted continuously that

the 2lst Century is the "Century of Africa." The issues which our nation,

along with all African nations, is encountering are numerous and difficult.

Despite this, I am determined to strive even further for the development

of African countries, to respond to SGI President Ikeda's expectations.